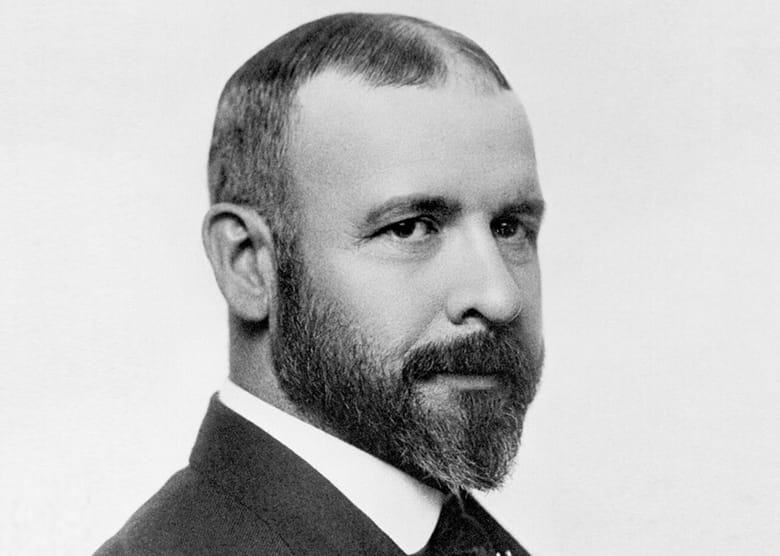

Louis Sullivan

Portrait of architect Louis Sullivan, circa 1895, via Wikimedia Commons

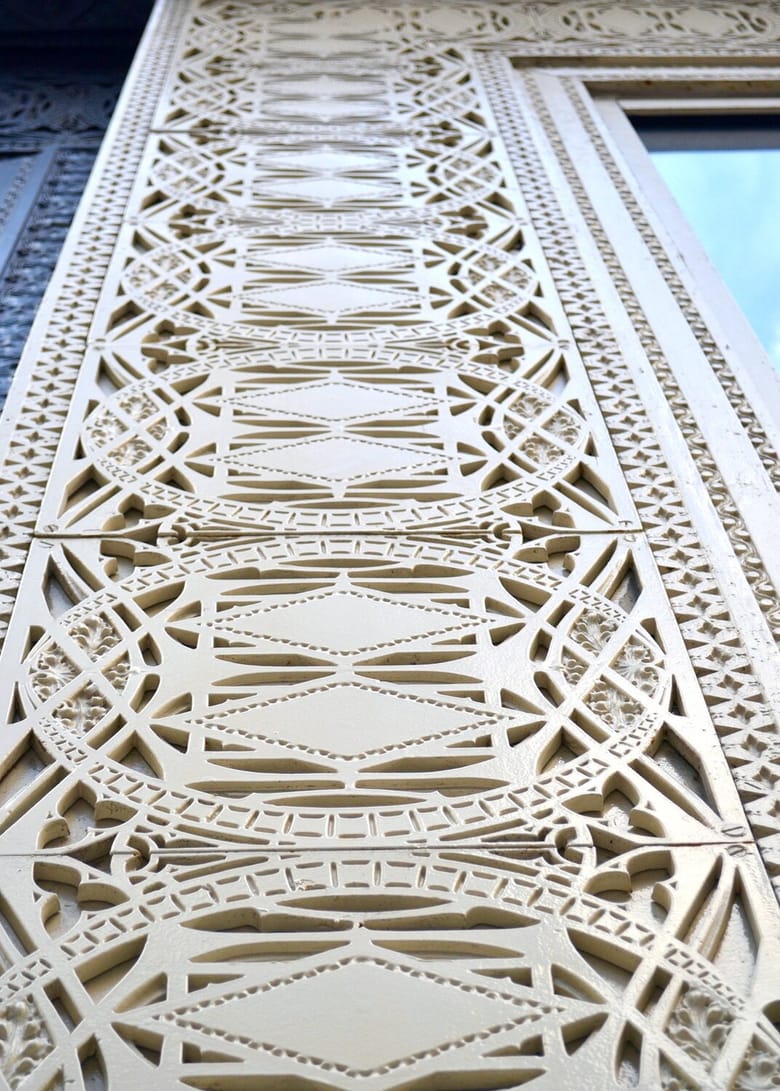

Auditorium Theater

As an architect, critic and mentor, Louis H. Sullivan had an impact on architecture that extends well beyond his work in Chicago. From the globally recognized phrase “form ever follows function” to the mentorship of a young Frank Lloyd Wright, Sullivan’s influence set in motion some of the most important ideas in modern architecture.

While working for various firms, Sullivan’s early years were marked by frequent changes to the course of his education. At the age of 16, he began his architectural studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston. After only a year, Sullivan left MIT and went to work for the architectural firm of Furness and Hewitt in Philadelphia. Shortly thereafter, the economic panic of 1873 set in, causing work to slow and forcing Sullivan to find employment elsewhere.

Seeking new opportunities, Sullivan made the move to Chicago in 1873. His timing couldn’t have been better. The Great Fire of 1871 had left the city’s central commercial district in ruins. As Chicagoans recovered from the fire, Sullivan found work with prominent architect William Le Baron Jenney. After a few months with Jenney, Sullivan was still eager to continue his education; he’d soon set sail for the École des Beaux-Arts, an influential school of art and architecture in Paris.

Upon his 1875 return to Chicago, Sullivan spent time with several firms but finally joined architect Dankmar Adler’s practice in 1879. There, he began a prolific career that would lead to Sullivan becoming a partner in 1881. Adler and Sullivan completed more than 100 projects during their 14-year partnership, including the now-demolished Chicago Stock Exchange and Garrick Theater. The massive Auditorium Building on Michigan Avenue—the largest, tallest, heaviest and priciest building of its era—stands today as one of the firm’s masterpieces.

Sullivan’s work rejected borrowing classical Greek and Roman elements so popular with many other architects of his day. This, combined with the influence of both Furness and Jenney, as well as architect H.H. Richardson, led to Sullivan’s own singular style. As Sullivan himself put it, “All things in nature have a shape, that is to say, a form, an outward semblance, that tells us what they are, that distinguishes them from ourselves and from each other.”

Through his exploration of organic ornamentation and steel-frame construction, Sullivan became a vocal advocate for the development of uniquely American architectural forms. He used natural ornament as a metaphor for a democratic society. For Sullivan, a building should respond to its own particular environment, just as a plant would grow “naturally, logically, and poetically out of all its conditions.”

Soon after his partnership with Adler ended, Sullivan designed the tripartite Schlesinger & Mayer department store in 1899 (known today as the Sullivan Center) at State and Madison streets in downtown Chicago. Sullivan’s use of cast-iron ornament inspired by nature along the building’s first floor and sculptural white terra cotta in the middle and upper floors, illustrates many of his theories on the design of tall buildings. Sullivan’s passing in 1924 left behind a remarkable legacy of buildings throughout the Midwest. He is buried in Graceland Cemetery on Chicago’s north side.