Ida B. Wells Housing Projects

The Ida B. Wells Homes were a series of rowhouses, mid-rise and high-rise apartment buildings to house Black families in the heart of Bronzeville.

The Ida B. Wells Homes were a series of rowhouses, mid-rise and high-rise apartment buildings to house Black families in the heart of Bronzeville.

Location: Bronzeville, 35th- 39th, Cottage Grove to Martin Luther King Blvd.

Completed: 1941

Style: Row houses, mid rises and high rises

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862-1931) was a Black female journalist, teacher and civil rights leader. She was born into slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi, and gained her freedom through the Emancipation Proclamation. Wells came from educated and political parents. After gaining their freedom, Wells’s father became a trustee of Shaw College (now Rust College), which is the same Historically Black College/University (HBCU) that Wells graduated from. She went on to become a teacher in Memphis, Tennessee, while also covering racial segregation and inequalities through the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper. She bought a share in the newspaper and became the first female co-owner and editor of a Black newspaper in the United States. While in Memphis, Wells also attended sessions at Fisk University and LeMoyne-Owen College, both HBCUs.

During her time in the South, Wells wrote for her pamphlet, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases, where she covered the lynching (the murdering of folks, usually hanged, without due process and legal trial) of Black bodies. She called out how horrible the practice of lynching was and how it was used as a fear tactic to keep African Americans from gaining success and equality. After her writing was disseminated nationally, a racist mob burned down her office. The last straw, and what ultimately brought her to Chicago, was the lynching of three good friends and store owners of People’s Grocery Company in 1892.

She didn’t let her move deter her from her fight against lynching. In Chicago, she continued reporting, organizing, and advocating for civil rights and women’s rights. She extensively documented 728 lynching cases between 1884 and 1892. Her investigations and research culminated in the 1895 publication of The Red Record, a 100-page pamphlet that detailed the prevalence of lynching in America. Women’s rights and suffrage were also focuses of Wells’s advocacy. She created some of the only safe spaces for women of color to organize and gather, including the Alpha Suffrage Club, the first African American women’s group that advocated for their collective right to vote. Along with the great Frederick Douglass and other Black leaders of the time, she also protested the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (often referred to as the Chicago World’s Fair), for its lack of Black representation. After this, Wells worked for the Chicago Conservative, the oldest African American newspaper in Chicago. Along with her civil rights work, Wells fought for the Chicago Public Schools to officially desegregate, as she saw firsthand that integrated schools offered more opportunity and resources to Black students. She also helped in the election of Oscar De Priest, the first Black city alderman of Chicago, and even staged her own campaign running as an independent candidate for the Illinois State Senate.

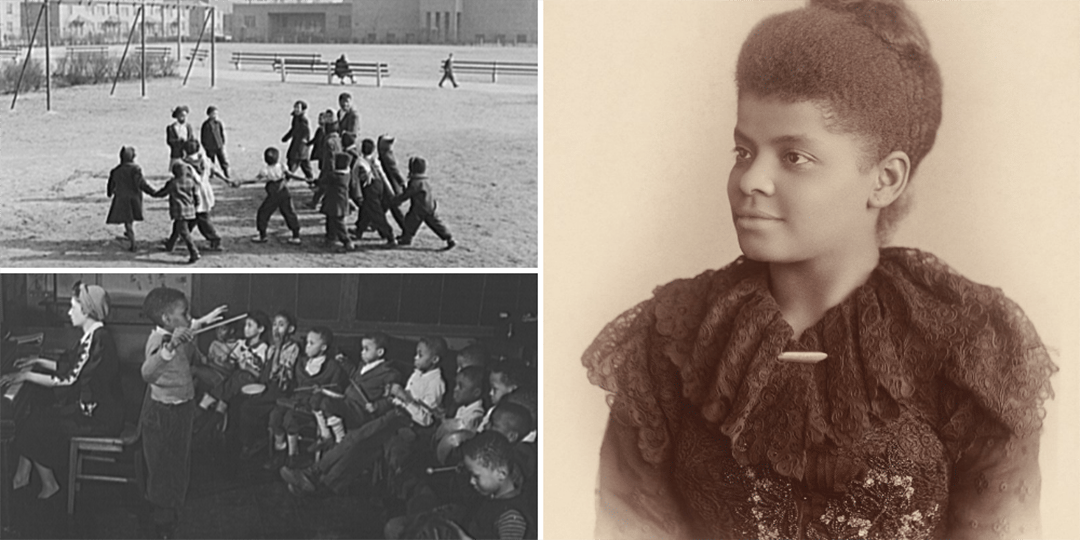

Named after Wells, the Ida B. Wells Homes were a series of rowhouses, mid-rise and high-rise apartment buildings, constructed in 1941 to house Black families in the heart of the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. When the homes first opened, more than 18,000 families applied to live in the 1,600-unit complex.

The occasion garnered strong media attention, including a 20-page special section in the Chicago Defender, a significant African American newspaper founded in 1905. Early Chicago Housing Projects, including the Wells Homes, were widely considered to be resources of upward mobility, lifting many residents to the middle class by providing first rate housing and a close community. However, due to many factors, including years of neglect by the city, the Wells Homes would eventually face demolition between 2002 and 2011. Today, The Light of Truth Ida B. Wells National Monument sits on the site of the Ida B. Wells Homes. The monument was largely funded by online donations spearheaded by a grassroots campaign by Wells’s great-granddaughter, Michelle Duster. While the homes no longer stand, the monument continues to shine a light on Wells’s incredible legacy and her fight for justice.

Additional Resources

National Women's History Museum Biography

New-York Historical Society: Life Story

Library of Congress: Topics in Chronicling America

Library of Congress Image Gallery of Homes (Interiors and Culture)

Library of Congress: Image Gallery of Homes (Exteriors)

South Side Weekly: The Overlooked Legacy of Ida B. Wells

The Chicago Reporter: How Ida B. Wells finally got the recognition she deserves in Chicago

The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States