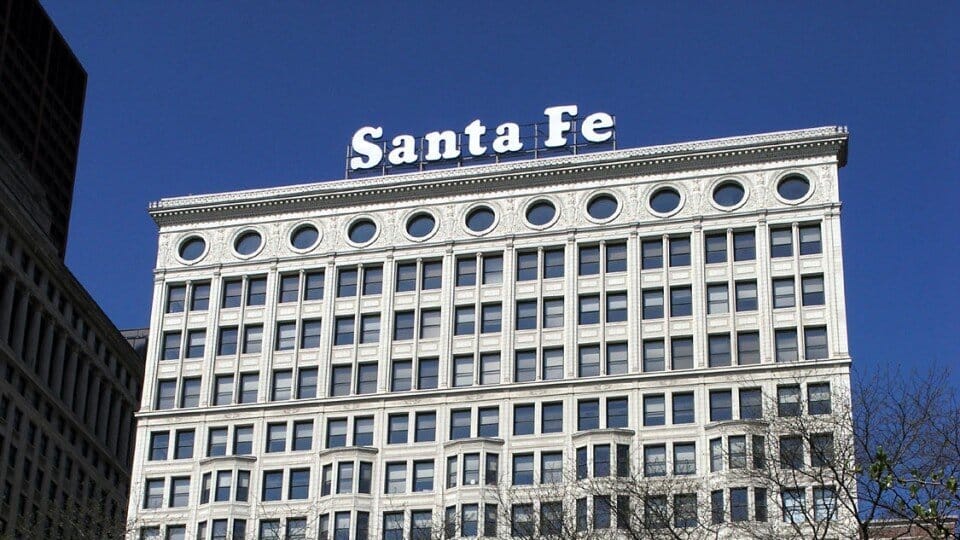

The Santa Fe sign

For years, a Santa Fe sign was perched atop the Railway Exchange Building on Michigan Avenue. What happened to those big white letters?

For years, a Santa Fe sign was perched atop the Railway Exchange Building on Michigan Avenue. What happened to those big white letters?

by Jessica Cilella, Web Editor

At the turn of the 20th Century, the Santa Fe Railway sought a downtown headquarters in Daniel Burnham’s newly built white terra cotta skyscraper at the corner of Jackson Boulevard and Michigan Avenue. With six train passenger terminals downtown and 15,000 people employed by the railroads, Santa Fe wasn’t alone in its need for affordable office space. The 17-story building, named the Railway Exchange Building, became home to Santa Fe and several other railroads, including The Alton Road and The Milwaukee Road.

Over several decades, Santa Fe acquired more ownership of the Railway Exchange Building. In 1946, it opened a street-level ticket office in the southeast corner of the building, complete with murals of desert and canyons to promote train travel to the American Southwest. But it wasn’t until 1954 that the railroad fully controlled the building. Federal Sign and Signal Company installed the first Santa Fe sign on the roof in 1962. Originally blue and yellow with illuminated neon, it measured more than 70 feet long and featured a 22-foot diameter Santa Fe cross logo to the left of the letters. In the 1980s, the railroad led an extensive remodeling of the Railway Exchange Building that included a sign replacement. The new sign was nearly identical, but made of toned down white Plexiglas. The capital letters were 12-feet high and the lowercase letters were 8-feet high.

The railroad left the building in 1991 and set up an office in the suburbs. In 1995, it moved to Fort Worth, Texas, around the time it merged with the Burlington Northern to become the BNSF. Still, the sign remained, becoming a familiar sight on Michigan Avenue.

“Everyone noticed the sign. It was a very prominent part of Michigan Avenue and downtown Chicago,” Jack Barriger, a retired Santa Fe Railway vice president, said in a video produced by the BNSF in 2016. “It made us—we Santa Fe employees—proud to be part of that.”

The creation of the Historic Michigan Boulevard District in 2002 included the Santa Fe sign. It stated that if the sign were removed, no replacement was allowed. Yet, in 2012, the building owners announced the letters would be coming down and Motorola’s name would be going up, as the company was acquiring naming rights with its move from a suburban office to the sixth and seventh floors of the building. The Chicago Landmarks Commission approved the removal of the Santa Fe sign and its Motorola replacement with the rationale that the Santa Fe sign was “not historical.”

The Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois—about 60 miles northwest of Chicago—immediately expressed interest in taking the dismantled Santa Fe sign. Other institutions asked for it too, including the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, but ultimately the museum was named the recipient. In the meantime, a new Motorola sign in the same white and blue style as the Santa Fe sign was installed.

The Santa Fe sign arrived at the Illinois Railway Museum in 2012 and sat in a barn for years while research into its restoration was ongoing. BNSF agreed to pay for its repairs and the construction of a new sign display, but it wasn’t until 2016 that the blue and white letters saw the light of day again. They were transported to MK Signs in Chicago, where more than 250 hours went into cleaning and repainting them. Workers added polycarbonate and wire to the letters, along with more than 1,400 energy efficient LED lights. In August 2016, the restored letters were mounted on new steelwork outside the museum. Dozens of train enthusiasts grateful for the sign’s preservation attended a relighting ceremony two months later that marked the official completion of the sign’s installation in its new home.